I once had someone tell me:

“Hari, you’re essential to this company, and we might have died if not for you. But we’re founders and you’re not, and nothing you do can change that.”

That single sentence shapes the entire way I think about the people at a startup: founders, founding team, early employees, and everyone else.

Until the 1990s in Silicon Valley…

… being a founder was the toughest job around.

It wasn’t cool to be a founder back then. Everyone thought “entrepreneur” was just a fancy way of saying “unemployed.”

The greats busted their ass in the proverbial garage for years until they shipped something. They didn’t have AWS or a million open source libraries. They set up servers to run that shit, and built their databases and components from scratch.

They tried desperately to recruit early employees because no one wanted to give up their cushy job. Even if they could find the rare person who wanted to change the world, the company was (probably) going to fail and they would get yelled at by their SO or their parents for wasting their life.

There were very few VCs, so capital was precious. Founders had to give up onerous terms during fundraising, because they had no power. 3x liquidation preference + participating preferred was the norm back then.

Starting a company and finding product-market fit is hard enough. Imagine if it was this much harder.

And so, those who had the courage to start something in the face of such immense adversity, were celebrated once they succeed. They were truly one in a million. Special.

Today, founders are still treated in a class of their own

The world has changed a lot in the last 30 years.

Virtually any founder(s) — assuming one of them can code — with the glimmer of an idea, can raise millions of dollars before there’s a product or revenue.

Creating a prototype has never been easier. Literally a weekend project.

Yet… “founders” are more celebrated than ever. Adored, even.

I don’t think I truly understood this until I became a founder myself. As a founder of a pre-seed startup in 2019 who had accomplished exactly nothing to date, I suddenly had access to VCs and invitations to exclusive events. Way more than when I’d been a non-founder-COO who had been critical to building a successful Series B startup.

It’s like moving up from economy to business class. Except I’d paid in blood, sweat and tears for that economy ticket; and I’d managed to enter business class simply by putting on a suit and walking in like I belonged.

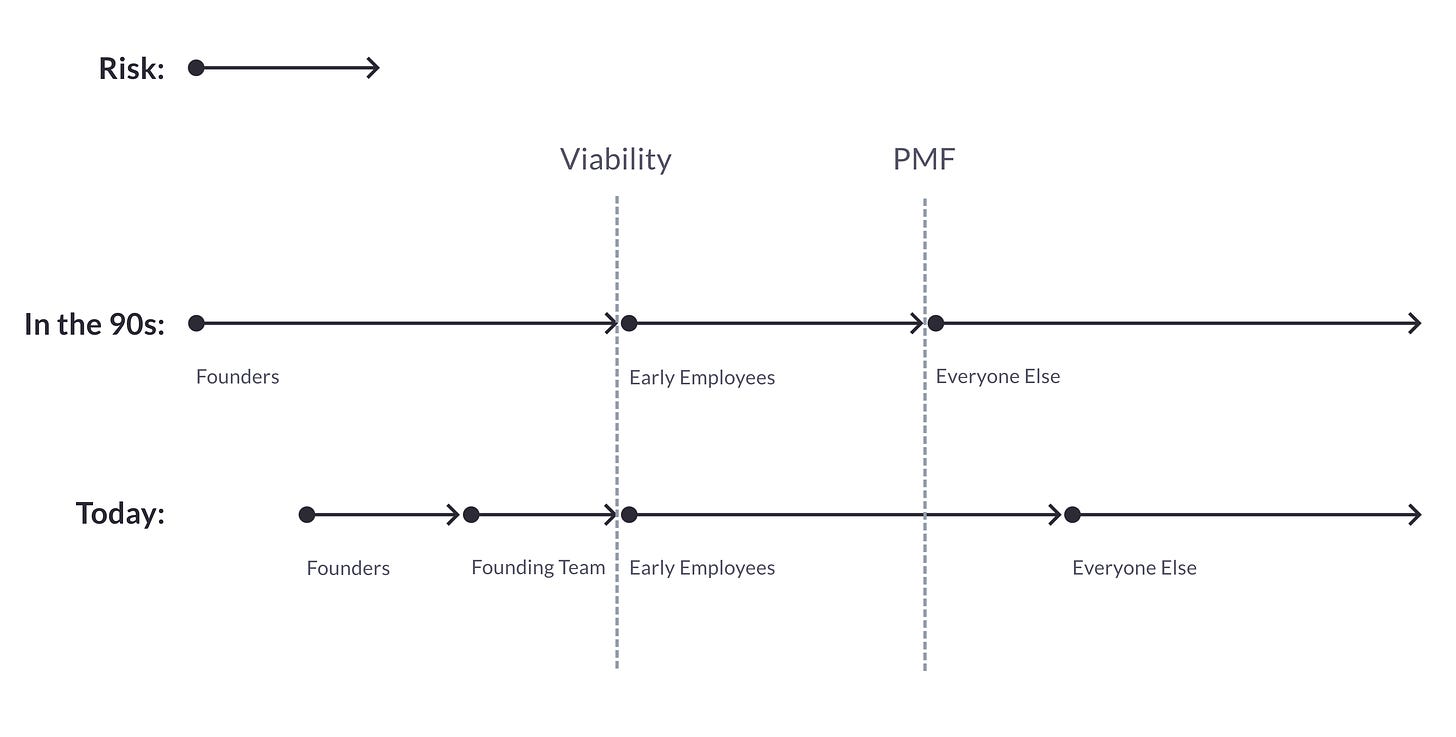

The burden of building has shifted from “founders” to “founders & founding team”

When early employees join a startup today, they’re not joining a de-risked company with PMF.

They’re usually joining a company with a Figma prototype and a bunch of money in the bank.

Don’t get me wrong. The money is important. It means they aren’t working for peanuts like some early employees might have, back in the day. A staff engineer or head of operations at a seed stage company is usually making $140-180K base in SF / NY. That capital is incredibly valuable because it buys time to build and sell things.

And the founders either had a lot of credibility, or undertook a herculean effort to raise that capital. Raising money is not easy.

But the risk from that point on is not that different from that of a founder. 99.9% of the hard work is still ahead.

Which means that early employees, particularly “ex post facto founders” (h/t Jason Lemkin: early employees or execs who shoulder “founder-like” burdens), are — according to current norms — left with the worst deal in the ecosystem, when it comes to equity, respect, and influence on a risk-adjusted basis.

Here is a list of things that founders are subject to, that early employees don’t have to deal with:

Months spent in the wilderness, exploring if the idea can even become a company1

Reputational & social capital risk with investors & employees

Here is a list of things that both founders and ex-post-facto cofounders take on:

Reputational risk with partners, suppliers, customers

Day-to-day stress of success and failure

Stress of shielding junior / rank-and-file employees from the ups and downs

Here is a list of things that all early team members (founders, execs, and early employees alike) take on:

Lost opportunity cost of making a “market” salary

Risk of product-market fit

Brand risk2

In return, founders make 1-2 orders of magnitude more equity; typically control the company through board seats and super-voting rights, and several orders of magnitude more recognition in the ecosystem for their role in the company.

Here’s a visual to make it clear. Founders deal with some of the worst parts, and get some of the best perks. Later-stage employees deal with the best parts, and don’t really get any of the perks. You see lots of red and green in those columns.

But why are we okay with a sea of orange and yellow for the columns in the middle?

Of course it’s hard being a founder. I’m just saying that it might not be 10-100x times as hard, which is what the equity, voting rights, and recognition would imply. Take two co-founders with 30% each at a Series A, four years in. The apportionment would imply that they were each twenty times as valuable as the next strongest employee, and three to five times as valuable as all 20 employees to date, combined. If you’ve started or helped build a company before, you’ve hopefully learned that this is pretty much never reality. This is why nothing frustrates me more than accepting “first employee gets 1%” like it’s gospel.

Being a founder is harder than any other role at the company. (Most) founders earn every bit of the money and credibility they get.

So this is not about tearing down founders. Hell, I’m a founder now.

This is about putting the founding team, ex post facto founders, and early employees where they belong.

This ends up hurting both sides:

Companies get hamstrung and have to deal with too many transitions, because many of the best early employees leave 3-4 years in, very consistently.

There are too many companies being started, because lots of people with an entrepreneurial streak end up starting something even if they would have otherwise opted to be an early employee… because being an early employee is just such a bad deal.

OK, so now what?

Here are a few suggestions; many are controversial, so pick and choose what you like. Any of them would be a step in the right direction towards a trusting relationship and celebration of those who enabled the company in its earliest days:

Be generous with honorary titles.

Apparently Jack Ma made every one of his early employees a “co-founder” of Alibaba. They had like 17 co-founders. I’m not sure if we need to go that far, but I love the push behind the sentiment… personally, I’m trying out co-founder, founding team, and early employees. And if someone establishes a function — e.g., sales — give them the benefit of “founding head of sales” or “founding designer”.

Allow people to get promoted into these honorary titles.

It’s normal to promote high performers with title and compensation, so why not here? For example, someone starts as founding team and knocks it out of the park (i.e., behaves like an ex-post-facto cofounder), honor it by promoting them to co-founder status one or two years in. If someone is an early employee (or a ridiculously strong exec) but earns it, make them a co-founder or founding team later on. Notion did this their COO, Akshay Kothari, and Rewind did this more recently with Paul Stamatiou.

Being a cofounder shouldn’t give anyone immunity.

Underperforming co-founders shouldn’t get to coast or rest-and-vest. Such breakups are hard, but it’s even worse for morale if you let cofounders play by different rules or be held to a lower standard.

Get more generous with early employee equity.

Get rid of this silly 1% benchmark for first employee.

Set up a dedicated “founding team pool” of 10-15% in restricted stock for the first 5-10 employees. Grant your first few employees several percent (at least); and if you want to trust but verify, split it across multiple “promotion” grants issued upfront, or set up a 6-year / 5-year vest for them.

That way, your early employees can look at your 25% to their 4% and feel that it’s at least in the ballpark of reasonable. The founders would still each get perhaps twice the equity of the first 5 employees combined… but it starts to approach a “fair” setup.3

Institute friendly equity management policies

Early exercise and / or an extended exercise window. The reasons not to do this are administrative and dumb, so push back on your lawyers if they tell you not to do this. (Not legal advice.)

Earmark restricted stock for your founding team, not options. Your early employees deserve as “cheap” an exercise as possible for the risk they took.

Founders and early team members should play by the same rules when it comes to liquidity. If there is a secondary in a financing round, founders, founding team, and early employees should get to participate in proportion to their (vested) holdings.

Once the company crosses certain milestones (5-6 years in, Series C/D+), get more friendly to secondaries. If you don’t, they’re going to happen anyway in quiet handshake deals, and the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t.

None of this stuff is rocket science! Just… Reward people in proportion to their contribution.

A neutral third party should be able to take a fresh look at the arrangements and say “yeah that seems okay.” Because right now, it’s a deeply skewed incentive and reward system.

Startups innovate all the time. Let’s apply some of that creativity to treating critical teammates the right way.

This is very variable. This “early journey” used to be years and very impoverished. Today, it could be a long time, or sometimes just a couple of months.

If you’re skeptical, ask early employees and execs at Theranos if they’re dealing with this, despite the fact that most of them were blameless.

Caution: this can introduce some complications with option pool negotiation during a financing round, “dead equity” concerns, etc. – it really depends on your situation and your investors, so handle with care.

The founder - early employee equity gap is too large. One aspect that justifies it not discussed here is there is an expectation that a founder never quits, while there's an expectation that an employee gets what they want from an experience and moves on their next thing (or leaves if the startup is not performing).

This is obviously not enforced, but this is the social expectation that means founders do take a significantly larger psychological burden. Ideally this expectation is reflecting in a vesting or reverse vesting schedule